--- Plumber, Son, Brother, Uncle, Hero ---

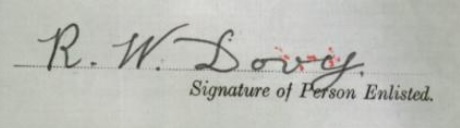

Signature of Reginald Walter DOVEY from his WWI enlistment papers.

Courtesy of the National Archives of Australia

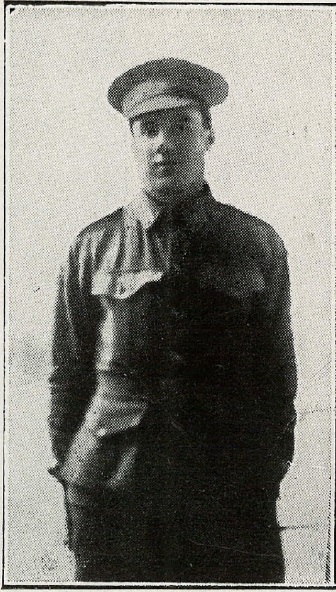

Title image: Reginald Walter DOVEY.

Courtesy of Australia’s Fighting Son’s of the Empire

Birth and Early Life

Reginald was born on the 4 October 1896 in Rokeby Road Subiaco to Frederick and Eleanor DOVEY (nee MOORE). He was the third child and second son born to the couple. Reginald had four siblings, but one sister, Emily would only live for little over a year, dying in November 1901.

Reginald’s parents had met and married in Brunswick, Victoria in 1886, at which time his mother Eleanor was a dressmaker and his father Frederick was a cabinet maker who had been born in London England. No documentation has yet been found that shows when Frederick Dovey immigrated to Australia.

Reginald spent his early childhood and school days in Subiaco, attending Jolimont Primary School, which only had 26 students when they opened on their current site[1] in 1905[2].

Life in Victoria Park

The Dovey family moved to Victoria Park sometime during 1910 and moved into the house that the family would call home until 1922. It would also be the home that two brothers would leave from to go to war, saying goodbye to their childhood and stepping out for what they probably believed to be a great adventure in the making – World War I.

The house never had a street number in records available to us, but it was in Albert Street (now Swansea Street), close to the Welshpool Road end of the street. The property was also big enough to hold livestock as the family had at least a “red cow and heifer” that strayed from the property in March[3] of their first year in residence. How different this light industrial and residential area is today from farming land of the time when the Dovey’s lived there.

Reginald turned 15 in 1911 by which time he was most likely undertaking his training as a plumber, his occupation at the time of his enlistment.

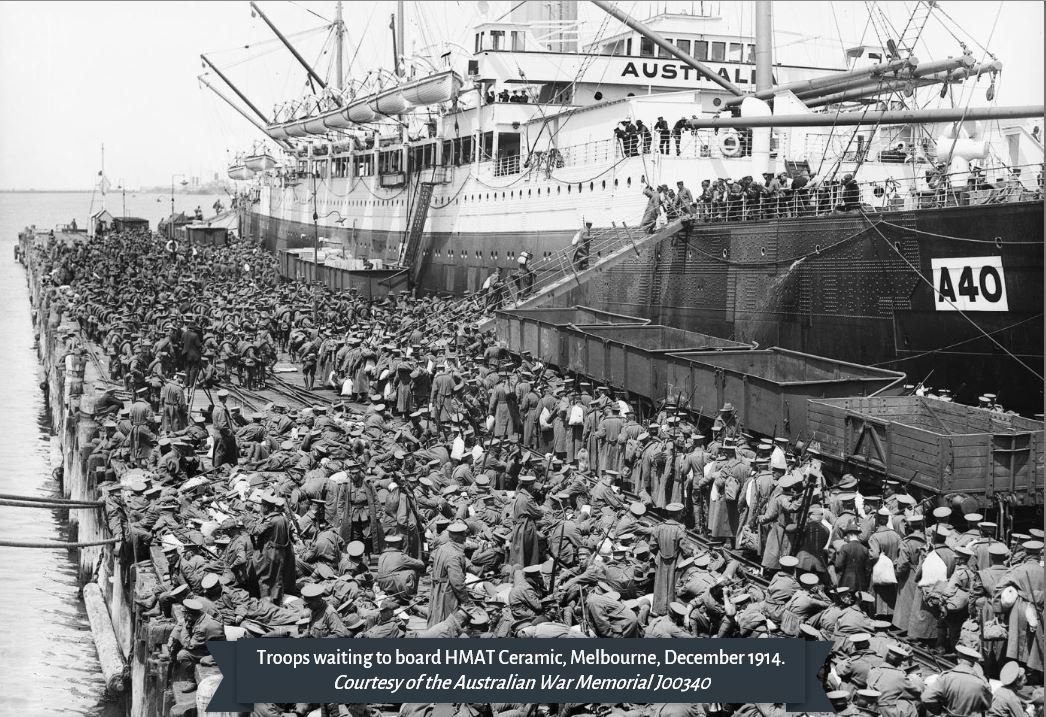

Reginald embarked for service at Gallipoli from Melbourne aboard the HMAT Ceramic. Courtesy of the Australian War Memorial.

World War I

Reginald enlisted in the Australian Imperial Force on 8 September 1914, first serving in the 16th Battalion as part of the Mediterranean Expeditionary Force (Gallipoli Campaign). He was wounded on the 28 April 1915 then suffered further injury and was hospitalised for a gunshot wound to the buttock on 6 May 1915. He returned to his unit at Gallipoli on 7 June 1915. Reginald would again suffer injury, this time to his eyes and was sent to hospital in Alexandria, Egypt on 2 July 1915. He spent most of August in a convalescent camp in Helouan. By late August 1915 Reginald was well enough to rejoin his unit in Mudros.

On 9 March 1916, Reginald was transferred to the 4th Machine Gun Company at Tel-el-Kebir, Egypt. The unit embarked from Alexandria to join the British Expeditionary Force in France on 1 June 1916, disembarking at Marseilles, France on the 9 June 1916. Reginald was promoted up the ranks several times from 3 June 1916 up to the rank of Sargeant on 7 September 1916. Suffering another sickness in late January 1917, he spent 52 days in hospital, returning to his unit on the second Anzac Day, 25 April 1917. Engaged in the muddy battleground that was France, Reginald fought valiantly on with his mates. His talents were recognised by those in command and on 26 August 1917, Reginald was detached to the Machine Officers Cadet Battalion in England and promoted to 2nd Lieutenant. Whilst in England, Reginald also attended the Machine Gun Course at Grantham, which he successfully completed on 19 December 1917. Unfortunately, he would again spend time in hospital with an illness, but regained his health and returned to duty in England in January of 1918. One imagines that the slight reprieve from the rigours and constant barrage of danger, would have also lifted Reginald’s emotional strength. He embarked from England on the 26 March 1918 to return to his unit the 4th Machine Gun Battalion in France on 1 April 1918, they were serving on the Western Front.

Reginald was promoted to Lieutenant on the 10 May 1918.

A Brother’s Story

Reginald’s older brother Frederick George Harold DOVEY, enlisted in the Australian Imperial Force on the 25 February 1916. To avoid confusion with his father, he was known as Harold DOVEY, and was single at the time of his enlistment. He had been a greengrocer and fruiterer by trade. By August 1916, Harold was fighting in France on the Western Front, just like Reginald. It is not known however if their paths crossed during their service.

Private Harold DOVEY (AKA Frederick George Harold DOVEY). Australia's Fighting Sons of the Empire, p. 137.

On the 16 April 1917, whilst Reginald was recovering from illness in hospital, his brother Harold was reported as missing in action. Later it was discovered that Harold had been taken as a prisoner of war by the Germans. Harold would be captive in Germany for the remainder of the war. His service file includes a copy of a postcard sent home asking to be sent a parcel with some small comforts such as treacle, cheese and cigarettes. No doubt his family back home were glad to hear that their beloved son was alive if imprisoned, a small comfort when news of the fate, of his brother Reginald would reach the Dovey family at home in Albert Street, Victoria Park later in the war.

The Battle of Hamel and Our Hero’s Last Moments

The 4 July is of paramount importance in the calendar of every American, yet it should arguably be remembered for a different reason in the minds of every Australian also. On this day in 1918 the bravery and brilliance of the Allied forces, predominantly Australian, under the command of General Sir John Monash whose plan to deceive the Germans entrenched near Hamel, would become legendary.

The Battle of Hamel was a “well-planned successful limited Allied action on the Western Front, 4 July 1918. Designed to straighten the Allied line the battle was notable for the careful co-ordination of infantry, artillery, armour and aircraft. Two brigades of Australian infantry assisted by American troops, British Mark V tanks and exceedingly accurate artillery barrages, quickly overran German positions and took in action when Royal Flying Corps units dropped 100,000 rounds of ammunition to Australian machine gunners.”[4]

Parachute ammunition drop, stuck in trees of Vaire Wood near Hamel. Dropped on 4 July 1918, photo taken 5 July 1918.

Courtesy of the Australian War Memorial (4090362).

The war diary of Private Eric Giles MILLER (165a) an infantryman of the 43rd Battalion[5], contains an immersive description of events. Events that our hero, Reginald Walter DOVEY was taking an active role in as a member of the 4th Machine Gun Battalion.

Here is Private MILLER’s account:

“The Battle of Hamel July 4th 1918.

“Hamel was really a big battle reduced to small scale. There was massed artillery – such accumulation of guns great and small, as could have blown the Hamel area in dust to the skies, let alone clear the Germans from it; There were tanks, a vastly improved breed on the old originals; There was a most detailed scheme of aeroplane co-operation in every phase, from the drowning, by bomb dropping, of the noise of the approaching tanks, to the carriage forward by air of machine-gun ammunition after the battle.

“The attack was made by 3 brigades – the 6th on the right with the 21st and 23rd Battalions (Victorian); The 4th in the centre, with the 13th (N.SW), 15th (Qld) and 16th (West Aus), and the 11th on the left, with the 44th (West) 43rd (South Aus) and 42nd (Qld [looks like Zucind])

“The 15th Brigade (Vic) was to make a small local attack east of Ville-sur-Ancre; the whole Corps front was to assist with artillery fire to distract Hun attention from the point of attack; but even beyond this a general co-operative bombardment was arranged for several miles on the British and the French fronts left and right of the Australians.

“The opening of the attack at 3.10 A.M.: as seen from the Morlancourt Ridge above Vaux, was a weird and wonderful spectacle. The time was immediately before dawn after a perfect night of early summer – a fresh calm soft aired night such as would turn men’s thoughts to anything but war. What morn there was vanished early and shooting was only spasmodic by the guns of either side. Now and again an aeroplane of ours – no Hun machines were to be heard – droned overhead like a mammoth mosquito, passed on towards Germany, and in the distance delivered a little cargo of bombs. But on the whole the night was strangely still and pleasant as summer nights go behind the fighting lines in France.

“During the last few minutes prior to the attack, a thicker humming droned in the air – a string of our aeroplanes flying low to drown with their noise the rattle of the tanks over their last half mile to the front line.

“The aeroplanes did more than hum. They suddenly awoke Hamel in a blaze of explosion by dropping collectively several bundles of bombs fair into the middle of it. Fires broke out here and there in the houses. Then opened a slow bombardment from our artillery in which the trench mortars joined; this was not the real thing, but a preparatory smother of smoke shell. For a week or more before the battle the Australian guns had shelled the Huns with gas at exactly this hour – a plan to deceive them for this 4th of July morning, and to make them put on their gas helmets; only this time the guns fired smoke instead of gas, for the sake of the assaulting infantry. The smoke shell was really the most fascinating spectacle of the whole attack. The dim light before dawn enlarged and distorted the smoke clouds to monstrous shapes, which were lit up fully, and thereby the more terribly, by the flames of the bursts. Here and there a brilliant rocket soared up from the doomed lines, yet seemed to convey no serious note of alarm, merely warning perhaps of the supposed usual gas strafe. The Hun Batteries at auyrate, were not aroused. For the last moment the little corner of country there among the broad sloping valleys, and its population, the semi-somnolent battalions which the imagination could picture easily enough in their holes, seemed unaware of the mighty pole-axe poised to strike.

“Then, at the very moment, you could swear of the first awakening flicker of dawn over the horizon beyond, the guns, suddenly alert and changing tone, broke out into the salvo of the instant called Zero.

“There was a big boom from the first counter-battery gun, a 12-inch monster behind the ordered array of the smaller artillery, and the still morning air was thence forth torn and racked with noise. The previous slow succession of bursts along the German line, irregular, and rather careless, innumerable almost to the observer, now quickened and multiplied like electric sparks of the whole front. Vast billows of smoke rolled about with them, smoke so thick that it was impossible to say for ten minutes or so, whether or not the barrage advanced. Gradually the morning light improved and the smoke cleared, and Hamel village began dimly to stand out.

“A little later the contours of the ground were visible up to Vaire Wood and Accroche Wood and other timber above the high road on the plateau. A tank or two could be seen crawling near Hamel. The barrage dust smothered the village, lashed it furiously, and passed on. No vestige of any fighting going on – there was not yet light enough to reveal it, anyway, only a half-dark dead-seeming country side close below the hill, and a low vengeful trail of destruction sweeping slowly over it like a storm. In the wake of the barrage of the Australian artillery in that dawning light, there seemed, from the hill above, a striking stillness and silence; no fires, no movement, no sounds, no German shells even (strange to say), or very few.

“The fires in Hamel died down, and at the southern end at a housetop, waved on the faint breeze a flag, the tricolour of France. An officer of the 43rd put it there.[6]

“The silence of the German guns was the strangest thing, but there was good reason for it; any batteries which were not being dragged frantically, out of reach of the assault were being so drenched with our counter-battery fire of gas and high-explosive that they could not be served. Then the light rapidly improved, and the cloud and the pillar of fire which went before the Australian brigade, dropped over the edge of the ridge beyond Hamel. The skyline there moved with the crawling backs of tanks. Day broke, and a gathering of body of men could be seen on the ridge; prisoners. The objective must have been gained. Little columns of men trailed about the middle ground of the scene, laying wires, carrying up supplies, going forward as reliefs or to help dig in. Hamel quiet and still ; Vairie Wood – much feared place – silent as the grave not a shot being fired in all the valley or on all the river flats. It is already two hours after Zero and seems like only 5 minutes.

“What happened in the half light during that two hours is fairly simple telling. The smoke amply fulfilled its double object of deluding the Huns into the belief that is was gas, and in shrouding our advancing lines from the machine gunners. About Vaire Wood especially” [here entry ends abruptly. Subsequent pages can find no continuance of the account].[7]

The village of Hamel and the country in the direction of Corbie, seen from the trenches held by the Germans until the battle of Hamel on 4 July 1918. The enemy front line on the morning of the 4 July was on the crest of the hill in the middle distance but after the successful attack the trench in the foreground was occupied by the supports some 200 yards behind the new front line.

Courtesy of the Australian War Memorial (E02844B).

During the Battle of Hamel that 4 July 1918, Lieutenant Reginald Walter DOVEY was walking with the corporal and the men of his unit. They were both struck by a shell and killed instantly in a wooded area known as Vaire Wood, near the village of Hamel. Every other member of Reginald’s Company was wounded.

“When this Officer and gun team he was accompanying were nearing the final objective of the attack on the VAIRE WOOD Sector 4.7.18., a shell burst among the team, killing Lt. Dovey and the Corporal outright, and wounding all the other members of the team. He was buried where he fell, near PEAR TRENCH West of VAIRE WOOD (HAMEL).” Statement given by Lieutenant A. Chapman to the commanding officer of the 4th Australian Machine Gun Battalion.[8]

Reginald was just 21, he had never married, never had the chance to have children and start a family of his own, instead he had given his life to protect this nation’s freedom and the freedom that all man should possess.

Legacy

In the days following[9] the Australians heroic deeds at Hamel, much praise was received by General Sir John Monash from many powerful figures in the Allied cause. The praise he notes verbatim in a later published history of this campaign and others, was when Georges Clemenceau[10] visited. In the words of Monash:

“The most distinguished and most welcome of all our visitors, however, was Monsieur Clemenceau, the veteran statesman of France, who, in spite of the physical effort, immediately after the sitting of the Versailles War Council had closed, made haste to travel to the Amiens area, and to visit the Corps for the special purpose of thanking the troops. He arrived on July 7th, and a large assemblage of Australian soldiers who had participated in the battle, and who were resting from their labours near General Maclagan's Headquarters at Bussy, were privileged to hear him address them in English in the following terms:

‘I am glad to be able to speak at least this small amount of English, because it enables me to tell you what all French people think of you. They expected a great deal of you, because they have heard what you have accomplished in the development of your own country. I should not like to say that they are surprised that you have fulfilled their expectations. By that high standard they judge you, and admire you that you have reached it. We have all been fighting the same battle of freedom in these old battlegrounds. You have all heard the names of them in history. But it is a great wonder, too, in history that you should be here fighting on the old battlefields, which you never thought, perhaps, to see. The work of our fathers, which we wanted to hand down unharmed to our children, the Germans tried to take from us. They tried to rob us of all that is dearest in modern human society. But men were the same in Australia, England, France, Italy, and all countries proud of being the home of free people. That is what made you come; that is what made us greet you when you came. We knew you would fight a real fight, but we did not know that from the very beginning you would astonish the whole Continent with your valour. I have come here for the simple purpose of seeing the Australians and telling them this. I shall go back to-morrow and say to my countrymen: 'I have seen the Australians; I have looked into their eyes. I know that they, men who have fought great battles in the cause of freedom, will fight on alongside us, till the freedom for which we are all fighting is guaranteed for us and our children.' "[11]

The 4 July 1918, duly attested by the honoured French statesmen, did thus go down in the annals of not just Australian history but also World history, as a defining moment in the war, that deserves honoured status on every Australian’s calendar of important days.

The Dovey family would have one of their sons return to Australia on 3 March 1919. The other would lay in a grave that called to him on the 4 July 1918, in the now sacred soil of the French battlefield, a little piece of Australia ever on foreign soil.

His family paid tribute to their “noble son and brother. At rest.” in The West Australian:

“He died as few men get a chance to die,

Fighting to save a world’s morality;

He died the noblest death a man may die,

Fighting for God and Right and Liberty,

And such a death is immortality.”[12]

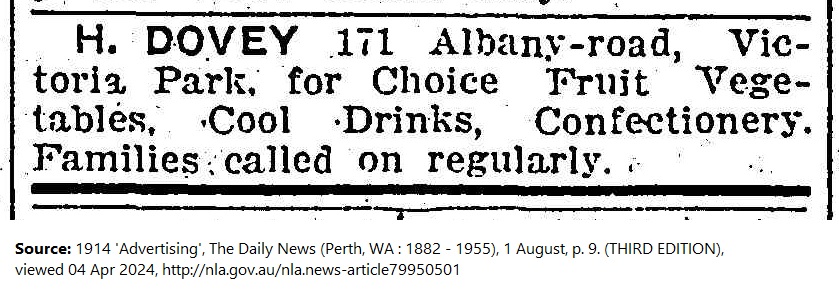

Harold Dovey returned to his business as a greengrocer that he had opened in 1914 and operated Dovey’s Store in a few locations[13] along Albany Road, Victoria Park until around 1924. Dovey’s Store also won a contract with the Repatriation Department in 1922 to supply fruit and vegetables to the soldiers recuperating at Edward Millen House. Even in peace time the Dovey family were looking after others. Following 1924, records say little of Harold Dovey’s occupation up until he became a factory hand and later a mill worker. Harold would marry and have three sons with his wife Edith, their first born of whom they named in honour of his fallen brother Reginald.

Around 1924 the Dovey family moved back to Victoria, where some would remain, but the majority of the family returned to Perth by the 1940s, with some living in Claremont, and Harold returning to Victoria Park for a while.

Around 1924 the Dovey family moved back to Victoria, where some would remain, but the majority of the family returned to Perth by the 1940s, with some living in Claremont, and Harold returning to Victoria Park for a while.

Reginald and Harold’s oldest sibling, Eleanor GIBSON (nee DOVEY) had four children and also named her first born son Reginald Harold GIBSON. Named, one would imagine, in honour of her two brothers.

Reginald had three known nephews who would take up the cause for freedom in World War II and carry on the legacy started by the brothers Dovey, the captivity of one and the ultimate sacrifice of the other.

At the going down of the sun,

And in the morning,

We will remember them.

Lest We Forget

Lieutenant Reginald Walter DOVEY.

Footnotes:

[1] 657 Hay Street, Subiaco WA

[2] Jolimont Primary School 2024, ‘History’, Jolimont Primary School website, accessed 3/4/2024, https://jolimontps.wa.edu.au/our-school/history/

[3] 1910 'Advertising', The West Australian (Perth, WA : 1879 - 1954), 30 March, p. 1. , viewed 03 Apr 2024, http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article26252960

[4] Australian War Memorial 2024, ‘The Battle of Hamel’, Australian War Memorial website, online, accessed 2/4/2024, https://www.awm.gov.au/collection/E84323.

[5] The original of which is held by the Australian War Memorial. A digital copy is available to read and to download from their website.

[6] As Private Miller was in the 43rd Battalion, he could even have been the soldier who planted the French flag.

[7] Miller, Eric Giles 1914-1917, [Wallet 1 of 1 – Diary written by Eric Giles Miller, 1914-1917], [Digitised copy of original diary], Australian War Memorial PR04312, accessed 02 April 2024, https://www.awm.gov.au/collection/C2615480.

[8] Australian Imperial Force 1919, [Service record of Lt. Reginald Walter DOVEY], B2455, National Archives of Australia, Canberra, p. 44.

[9] Georges Clemenceau addressed Australian soldiers on the 7 July 1918, to commend them on their actions at the Battle of Hamel.

[10] Georges Clemenceau was President of France from 1906-1909 and would be again from 1917 to 1920. Going on to achieve fame for his tough stance against Germany and her actions. He was a chief negotiator of the Treaty of Versailles.

[11] Monash, General Sir John, ‘Hamel’, in The Australian Victories in France in 1918, Hutchinson & Co., London, accessed online 3/4/2024, Project Gutenberg Australia, https://gutenberg.net.au/ebooks13/1302421h.html#ch-05.

[12] 1918 'Family Notices', The West Australian (Perth, WA : 1879 - 1954), 20 July, p. 1. , viewed 05 Feb 2024, http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article27484176.

[13] 171, 163 and 289 Albany Road, Victoria Park.

Bibliography:

1910 'Advertising', The West Australian (Perth, WA : 1879 - 1954), 30 March, p. 1. , viewed 03 Apr 2024, http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article26252960.

1914 ‘Advertising’, The Daily News (Perth, WA : 1882 – 1955), 1 August, p. 9. (THIRD EDITION), viewed 04 April 2024, http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article79950501.

1915 ‘Advertising’, Sunday Times (Perth, WA : 1902 -1954), 4 April, p. 25, viewed 15 Mar 2024, http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article58587535.

1915 'WESTERN AUSTRALIAN CASUALTIES.', The West Australian (Perth, WA : 1879 - 1954), 25 May, p. 5. , viewed 15 Mar 2024, http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article26943163.

1915, Western Mail (Perth, WA : 1885 - 1954), 4 June, p. 4. (ILLUSTRATED SECTION), viewed 15 Mar 2024, http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-page3489135.

1918 'Family Notices', The West Australian (Perth, WA : 1879 - 1954), 20 July, p. 1. , viewed 05 Feb 2024, http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article27484176.

1921 'Family Notices', The West Australian (Perth, WA : 1879 - 1954), 5 July, p. 1. , viewed 15 Mar 2024, http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article27968157.

The AIF Project 2024, ‘Reginald Walker DOVEY’, The AIF Project, University of NSW, Canberra, online, accessed 9 March 2024, https://www.aif.adfa.edu.au/showPerson?pid=82471.

Australian War Memorial 2024, ‘The Battle of Hamel’, Australian War Memorial website, online, accessed 2/4/2024, https://www.awm.gov.au/collection/E84323.

Jolimont Primary School 2024, ‘History’, Jolimont Primary School website, accessed 3/4/2024, https://jolimontps.wa.edu.au/our-school/history/.

Miller, Eric Giles 1914-1917, [Wallet 1 of 1 – Diary written by Eric Giles Miller, 1914-1917], [Digitised copy of original diary], Australian War Memorial PR04312, accessed 02 April 2024, https://www.awm.gov.au/collection/C2615480.

Monash, General Sir John, ‘Hamel’, in The Australian Victories in France in 1918, Hutchinson & Co., London, accessed online 3/4/2024, Project Gutenberg Australia, https://gutenberg.net.au/ebooks13/1302421h.html#ch-05.

National Archives of Australia: B2455, Dovey, R W, https://recordsearch.naa.gov.au/SearchNRetrieve/Interface/ViewImage.aspx?B=3518114.

State Library of Western Australia 2021, Wise’s Post Office Directories, online, H. Wise & Co., Perth, Western Australia, accessed multiple dates, https://slwa.wa.gov.au/collections/collections/post-office-directories.

Victorian Government 2024, Births Deaths and Marriages Victoria, https://my.rio.bdm.vic.gov.au/.

Western Australian Government 2024, Registry of Births Deaths and Marriages, Department of Justice, https://www.wa.gov.au/organisation/department-of-justice/online-index-search-tool.

|

This article was first published online in the Victoria Park Dictionary of Biography, Town of Victoria Park Library, April 2024. Written by Rosemary Ritorto, Local History Coordinator.

Reginald Walter Dovey was the 'Local Hero Focus Person' specially commemorated in the Town of Victoria Park's Anzac Day commemorations at Memorial Gardens, Albany Highway, Victoria Park on 25 April 2024.

Pick up a copy of his special commemorative brochure from the Library or download a copy to keep here: Dovey, Reginald Walter - 2024 ToVP Anzac Day Local Focus Hero Commemorative Brochure.

|