Published on Tuesday, 2 April 2024 at 10:46:09 AM

Welcome to #TimeWarpTuesday! This week we bring you ‘Part Two’ of the story of Edward Davis Millen. If you have ever wondered about the man behind the name of the heritage listed stately ‘mansion’ house that is known as Edward Millen House, then you will be in for a treat. The man himself was a man of adventure and passionate belief in providing our soldiers all they needed to return from World War I and integrate back into life as a civilian. Edward Davis Millen was a journalist, grazier, land agent, politician, senator, cabinet minister, husband, father, grandfather, patriot and friend to Australia’s soldiers. And contrary to popular opinion, he did visit Western Australia.

Edward Davis Millen (1860-1923)

Signature of Edward Davis Millen. Image taken from the first edition of ‘Repatriation’ the official journal of the Repatriation Department, Vol. 1, No. 1 (March 1919).Courtesy of Trove.

-Part Two-

Political Career

Edward began a long career of public service across many roles when he came to Australia, the following list provides some detail of them:

- 1885, 12 January – appointed Coroner at Brewarrina, New South Wales, and for the Colony generally [1].

- 1891 – Stood for election in the New South Wales Legislative Assembly in the seat of Bourke but lost.

- 1894 - Elected to the New South Wales Legislative Assembly in the seat of Bourke.

- 1894-1898 – Held the seat of Bourke in the Legislative Assembly.

- 1899, 8 April – Nominated to the New South Wales Legislative Council

- 1901 – Resigned his seat in the Legislative Council

- 1901, 14 May – 1923, 21 September - Elected to the first Commonwealth Parliament as a Senator for New South Wales. A position he held until his death in September 1923.

- 1907 – Appointed Leader of the Opposition in the Senate

- 1909, June – 1910, April – Vice-President of the Executive Council

- 1910 – 1913 – Leader of the Opposition in the Senate

- 1913, June – 1914, September – Minister for Defence

- 1914, September – 1917, February – Leader of the Opposition in the Senate

- 1917, February – November – Vice-President of the Executive Council

- 1917, September – 1923, February – Minister of State for Repatriation

- 1919 – Acting Prime Minister

- 1920 – Represented Australia at the Assembly of the League of Nations in Geneva

By far the greatest achievement of Edward in his political career would have to be his commitment to repatriating the Australian Soldier.

Senator E. D. Millen, N.S.W. c. 1910.

Courtesy of the State Library of Queensland

Friend to Soldiers

The government body that is now responsible for the care of returned servicemen and women, widows, and orphans, is known as the Department of Veterans’ Affairs, but when it began on the 8 April 1918, it was known as the Repatriation Department, and Senator, the Honourable Edward Davis Millen was the first Minister of Repatriation.

Prior to World War I there were no consolidated Australia wide program that could care for or fund the repatriation of her soldiers. There were many voluntary patriotic organisations and local communities that did their best to raise funds at the local level to support returning soldiers, but these could in no way meet the requirements of those returning from service in World War I.

Whilst Minister for Defence in 1914, Edward proposed that a scheme should be established which would allow for government-funded war pensions [2]. It wasn’t until May 1916 however, when the Australian Soldiers’ Repatriation Fund Act 1917 was passed, which helped in some small way, but there was still a lack of a centralised body to facilitate the work that needed to be done across the country. In April 1917 Edward proposed a new bill, which passed and became the Australian Soldiers’ Repatriation Act 1917. Edward became the Minister for Repatriation, and Australia was well underway to providing a comprehensive scheme that would allow for all returning soldiers to be assisted and cared for in their return to civilian life. It would not be an easy load to carry, but Edward carried it well and whilst he had not served himself, he undertook the role of Minister for Repatriation in the true spirit of the Australian Digger, he worked with dogged determination and patriotism.

Edward outlined his scheme for the repatriation of Australia’s soldiers many times, but the second reading speech of the bill in the Senate on 18 July 1917, gives a very good summary, of which the following is part:

“Repatriation, as we understand it, is an entirely new proposition, and, seeing that war is as old as humanity itself, it is perhaps strange that this so. But, though it has been said that the war is in some sense a failure of civilisation, we can yet see through it some of the triumphs of peace. The conception of repatriation as a national obligation reveals a new conception of public duty. When we remember that, and when we also recollect the splendid efforts which have been made to carry comforts to our troops and aid to the wounded – efforts going right up to the fighting line – we shall see that through this war is being revealed that humane and civilising process which quietly and unostentatiously, but nevertheless surely, marked that long peace which was so rudely broken in August 1914. Now, although much unrelated private effort has been made in many of the Allied countries, it is unquestionably true that up to the present no comprehensive scheme for the repatriation of returned soldiers has yet been submitted by any Government anywhere. Australia has on more than one occasion given a lead to the world. It may perhaps be regarded as a cause of satisfaction that it is doing so in connection with the repatriation of its soldiers.

“It is first of all necessary to arrive at a clear conception of what we mean when we use the word ‘repatriation’. Very many sincere and emphatic promises have been made to our troops, but they have been vague and indefinite to a degree. These, perhaps, expressed the state of our feelings rather than a clear line of action. It is necessary, therefore, that we should plainly set out what it is that we contemplate and what it is that we intend. In my view – and I venture the opinion in all humility – when we speak of repatriation we mean an organised effort on the part of the community to look after those who have suffered either from wounds or illness as the result of the war, and who stand in need of such care and attention. We mean that there should be a sympathetic effort to reinstate in civil life all those who are capable of such reinstatement. That is what we intend when we use the word ‘repatriation’. The nation put forward an organised effort to enroll [sic] these men in the ranks of the fighting army, and there must be an equally organised effort to secure their return to that civil life which at the call of duty they temporarily abandoned….I present them [the proposals of the bill] too, in the hope that they will be received as an earnest attempt to meet the nation’s obligations to those who on its behalf have gone down into the Valley of the Shadow of Death, and that they may be regarded as not altogether unworthy either of Australia or of those who heroically fought and suffered in its defence.[3]”

In this the second reading of the Repatriation Bill in the Senate on 18 July 1917, Senator Millen was unsurprisingly asked, by Senator Gardiner, “What about financing the scheme?” Senator Millen replied “I tell the Senate quite candidly that I am not at this juncture concerned about finance. I have put before honorable [sic] senators a proposition representing the duty we owe to these returned soldiers, and whether it is going to cost more or less for the discharge of that duty, we have to shoulder it.”[4]

The cost of Repatriation would go on to be a point of ongoing and heated debate both in Parliament and in the press, with much criticism laid at Edward’s door, but he never once allowed himself to dwell too long on negativity and the lack of perception of others but instead he chose to focus on the facts that more and more returned soldiers were re-entering the workforce each month and more and more were being trained. The Albany Advertiser (WA) reported in the 10 December 1919 edition that “Speaking on problems of repatriation in New South Wales, last week the Minister for Repatriation (Senator Millen) stated that a tremendous effort was being made by the opposition to pose as the friends of the soldiers. The Minister said the Labor Party were indulging in a lot of loose criticism regarding repatriation. Mr. Ryan charged that too little money had been spent. Repatriation, however, was not to be judged by the amount spent, but by the results achieved. It was not an institution for the mere scattering of money. In spite of the publicity given to complaints and errors he claimed that the department had done its work with a great measure of success. It was conceivable that those who were dissatisfied would become articulate, but the much larger number having no complaint, were silent. The country did not appear to recognise that if there was yet much to do, the back of the repatriation problem had been broken. Already 250,000 men had been returned to Australia, leaving only 13,000 yet to arrive, and 116,000 had reached these shores during the last six months – an average of 4,451 per week. Yet there were on the books of the department to-day, awaiting employment, only between 13,000 and 14,000 men, or equivalent to the average number returning ever three weeks. During the last six months this represented 7 per cent, which he claimed as a moderate percentage. …Provision had been made for technical training up to 20,000 men. Instruction was being given in 164 trades. Not only would this training be of great benefit to the men themselves, but he thought it was an asset to Australia to have 20,000 skilled men where previously there were 20,000 unskilled [5]”.

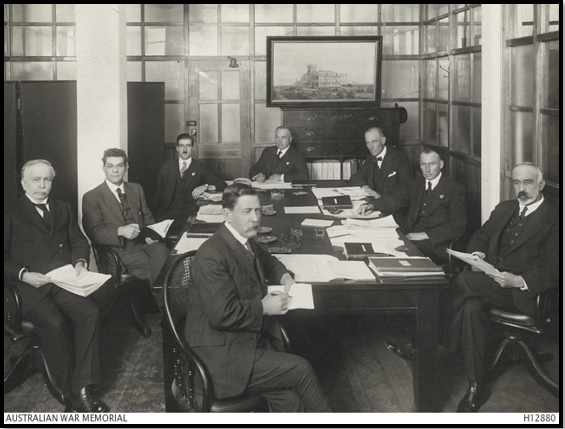

Edward Millen with members of the Repatriation Committee, first meeting May 1920. Courtesy of the Australian War Memorial.

Edward Millen House

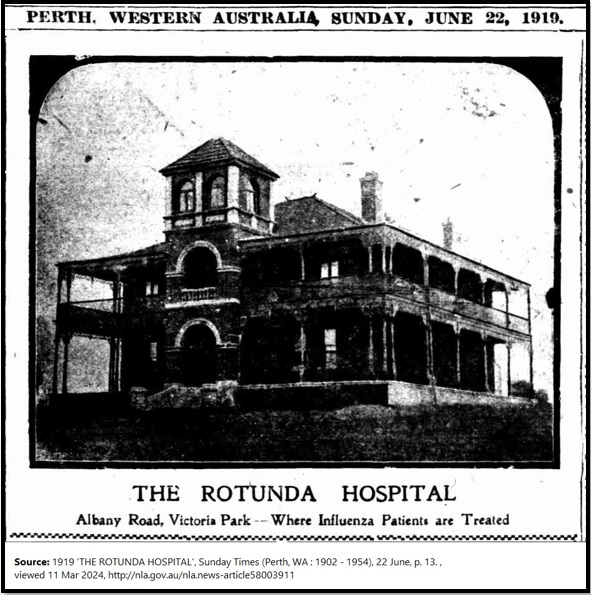

A beautiful stately building with iron-lace balustrading, and impressive tower room, rests amongst lush parklands reminiscent of the rolling green country manor grounds of England. In this setting, at the corner of Albany Highway and Hill View Terrace, East Victoria Park, sits a two-story building. The impressive Federation Queen Anne styled edifice is both a beloved local treasure and a building of high importance in the marking of Western Australia’s place in the history of health and medical care in Australia. The building of which we describe is that which was built in 1912 and opened as The Rotunda Maternity Hospital.

Elizabeth Baillie, a local midwife who was already practicing in Victoria Park purchased the land for £690 in 1911 [6], and proceeded to build the building we know today, basing it on the famed Rotunda Maternity Hospital of Dublin, Ireland. At the time the hospital was built, it was common for women to have home births, the establishment of the Rotunda Maternity Hospital changed this, and did so four years before the establishment of King Edward Memorial Hospital in Subiaco which would become Western Australia’s first public hospital for women.

In 1919 the world was reeling from the repercussions of war when the Spanish Flu, an influenza pandemic, struck. On the 7 June 1919, the State Government took over the Rotunda Maternity Hospital for the treatment of influenza patients, with the Perth Public Hospital managing the facility. It is known that 186 patients were treated for influenza at the Rotunda, “with an average stay of 13 to 22 days, and of whom 170 were discharged and 16 died. It has not been possible to establish whether the place returned to use as a maternity hospital after it was closed to influenza cases” [7].

Edward Millen Home, circa 1940.

Local History Collection, Town of Victoria Park Library Service.

-End of Part Two-

We hope you have enjoyed the second part of our look back at the life and achievements of Edward Davis Millen. Be sure to check back next week for Part Three (final), the Western Australian connection and a living legacy.

We are always keen to collect photographs, memorabilia, and other items related to the history of the suburbs within the Town of Victoria Park and can scan and return originals to you. If you have something you’d like to share, please reach out. You can get in touch with us via Ph: 08 9373 5500, E: vicparklibrary@vicpark.wa.gov.au, or by coming in.

#LoveVicPark #VictoriaParkDictionaryofBiography #EdwardDavisMillen

Footnotes:

[1] New South Wales Government 1885, NSW Government Gazette, January-March 1885, p. 398.

[2] Commonwealth Government 2011, ‘History of the Repatriation System’, in Repatriation Commission, Military Rehabilitation and Compensation Commission, Department of Veterans’ Affairs: Annual Reports 2010-2011, Department of Veterans’ Affairs, Canberra, p. 11.

[3] Millen, Edward Davis 1917, ‘Speech by the Senator The Hon. E. D. Millen, Vice-President of the Executive Council on the Australian Soldiers’ Repatriation Bill’, Parliamentary Debates, 18 July 1917, Victoria, Australia, p. 21. Accessed online from the National Library of Australia.

[4] Millen, Edward Davis 1917, op. cit.

[5] 1919 'REPATRIATION DEPARTMENT', The Albany Advertiser (WA : 1897 - 1954), 10 December, p. 4. , viewed 09 Mar 2024, http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article70141961

[6] Canning Location 2

[7] Stephen Carrick Architects 2021, ‘Edward Millen Hospital’, in Local Heritage Survey 2021, Town of Victoria Park, Victoria Park, Western Australia, pp. 142.

Back to All News